A Tale of Two Cemeteries

HEREsay #3: Walter Pater's Desecrated Grave

Oh! for a godlike aim through all these silent years.

- Walter Pater, ‘Oxford Life’

The Age of Wisdom, the Age of Foolishness

Growing up, there was a cemetery behind my house. Out past our sprawling backyard with its towering trees, their roots bursting through the soil.

The cemetery was small—smaller than my backyard—and teeming with chestnut trees. When you stood inside the cemetery’s boundaries, it felt as though there was nothing else around but you, the graves and the trees. Maine sits at the northern tip of the American chestnut’s native range but has more mature trees than any other state. The trees grow wild, flowering in summer, dropping their hoard of chestnuts in the fall. The edible nuts are encased in spiny burrs, but often poke out like thick tongues. Ready to entice wildlife and disperse seeds. About a month or so into the school year and I would hear the nuts drop, knocking softly against the graves and the growing beds of leaves. Hollow plops and pocks, like ghosts arriving home to throw keys on tabletops and piles of unanswered mail.

Two graves, slightly askew, stood out among the many Farnhams and Goulds. Though not particularly ornate, their surfaces bitten by acid rain, they read “Abraham Lincoln” and “Thomas Jefferson.” Not the ones you’re thinking of, surely, but the happenstance of two presidential names so close to one another in that little graveyard would cause me an eerie stir. Still does. Eerier still because Jefferson—the one you are thinking of—shared my day of birth: April 13. I’ve lived a life on the lookout for odd connections, and this was perhaps the first.

One autumn, as the school bus passed along the road on the far side of the cemetery, my friend and I plastered our faces against the bus windows, sure we had seen a stooped figure sweeping the leaves between the graves. Exiting the school bus, we tore through the short wooded path separating my yard from the cemetery, only to find the silent graves and overhanging chestnut trees. No man among the bed of leaves and split open encasements. Nothing being swept. Lincoln and Jefferson solemnly tipping their headstones in our direction.

The Epoch of Belief, the Epoch of Incredulity

Ever since childhood, I’ve been drawn to two things with unwavering consistency: coincidences and cemeteries. As much enamoured by the latter as I am terrified of what lies beyond death. Cemeteries are places of commemoration. Communal tips of the hat to transience, to all the ways we carve stones and leave flowers in our desperation not to believe what is going on beneath the manicured rows or bed of unraked leaves.

My enduring love of graveyards is why, when visiting Oxford in mid-February, I veered into Holywell Cemetery as soon as I spotted its entrance, which was half-obscured behind tangles of greenery and bare branches. Night was falling on the outskirts of the city center with its cornices and quadrangles, and there weren’t many people around. Nevertheless, I entered the dark bower without thinking, sending no alert to my husband up ahead. I passed an old keeper’s lodge behind construction fences and emerged in an overgrown graveyard ringed by trees and dotted with snowdrops that glowed in the twilight. Some of the stones seemed to appraise me, wondering who had come to disturb them. Others seemed to hold a finger to their lips.

The scene reminded me of a photo of Patti Smith as she stands over the grave of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in Cambridge, sunglasses on, white hair framing her face. Smith describes that cemetery as “a modest graveyard where nature reigns,” and I would say the same for Holywell. I snapped a photo of my own and ran to catch up with my husband who—used to my wanderings—was simply waiting at an intersection for my return.

The Season of Light

In the light of day, we returned to Holywell. Historian A.L. Rowse described coming upon the same shrouded entrance on a July walk:

“Quiet, a blessed stillness, only Sunday sounds – it might be the Victorian age – as I turn in under the shadow of St Cross and glimpse, embowered in its shrubberies, the little sexton’s house and church school, in the Gothic of the 1860’s, something straight out of Alice in Wonderland: latticed windows, overhanging eaves, porch buried under a rambler rose. But one would never have believed what treasures there are within – the whole of Victorian Oxford leaps to the eye from headstone to headstone.”

The evocation of Alice is apt. The likely inspiration for The Mad Hatter, Theophilus Carter, is buried in Holywell Cemetery. And among the “whole of Victorian Oxford” are at least 160 University dons (as Lewis Carroll was), including 32 Heads of Houses (a Head of House being a teacher who has the responsibility to guide all pupils in that House, much like how Professor McGonagall is Head of Gryffindor).

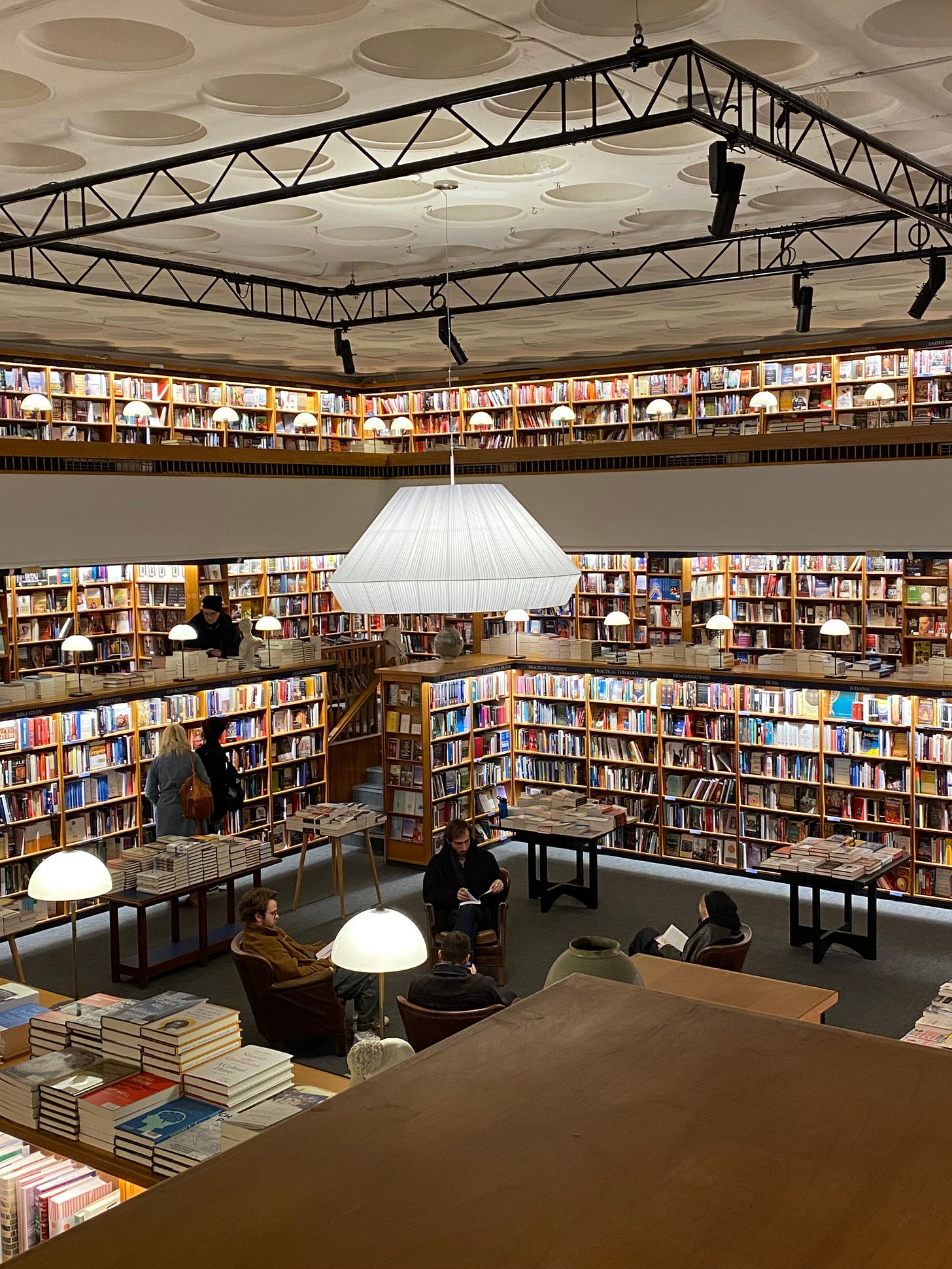

There is also at least one “eccentric” (Cuthbert Shields, who changed his name believing himself to be the reincarnation of St. Cuthbert) and many -ologists (a zoologist, papyrologist, Egyptologist), as well as shopkeepers and tradespeople. The list reads like a nursery rhyme, with a baker, a boatbuilder, a bootmaker and no less than two booksellers. One of those booksellers being Benjamin Blackwell (1814-1855). Bibliophiles will recognize that name. Blackwell’s is the immense, labyrinthine bookstore on Broad Street—a book lover’s dream. Benjamin was Oxford’s first city librarian and his little bookshop preceded his son’s much (much) larger store.

Holywell’s swelling ranks were the result of a growing population and mid-1800s outbreaks of cholera, with churchyards insufficient to keep up with the demands of the dead and those obliged to intern them. Even the chapel that was once on the site was demolished to make room and the restriction that cemetery denizens be baptised members of the Church of England had to be lifted soon after the cemetery’s opening—though the initial requirement is likely one reason why there are so many headstones in the shape of crosses. Over the years, caretaker funds dried up and wilderness encroached on the once “lovely garden full of trees and flowers.” In December 2022, hoping to stop the influx once and for all, the Secretary of State for Justice applied for an Order to discontinue burials. Today, maintenance of the cemetery falls to the Friends of Holywell Cemetery and willing volunteers, as well as the University of Oxford Parks team of gardeners and tree specialists.

Armed with two famous names from a map at the outset—Kenneth Grahame (The Wind in the Willows) and pioneering aesthete William Pater—I went in search. The University Church website calls Holywell Cemetery “a haven of tranquillity and recollection in a city where space and stillness are increasingly at a premium,” and a local fox seemed to agree. On the other side of a fence, the fox slept on a stack of cardboard boxes and trash bags it had dragged into a resting place. So, I had found one fox and eventually a Grahame but, despite combing row after row of graves, no Pater. As often happens in cemeteries offering general vicinities, finding specific graves lacked the finesse of GPS tracking. I peered behind clinging ivy and squinted at weathered stones. My husband wearied of the task and gave up trying for a spell—though he was eventually the one to pinpoint Pater’s resting place.

In doing research for this post, I found that Walter Horatio Pater (1839-1894) spent his childhood in Enfield, the borough where I now live. The kind of serendipitous link I crave. He would go on to write often about the bucolic beauty he saw there before moving on to Canterbury and Oxford, as well as the “dance of mutual solitude” he experienced with his family.

An essential part of the “Tragic Generation” shared by Oscar Wilde, Pater was an English essayist and critic who dabbled in fiction—a supreme stylist with an ‘art for art’s sake’ mentality. He has a dense, poetic style he crafted through arduous work and constant revision, writing ideas on little squares of paper and moving them around to create ideal arrangements, each sentence building to an overall ‘movement’ within the chapter or larger work. Rather than think of criticism as merely descriptive or judgmental, he was one of the first to apply psychology to the practice. Some have even accused him of simply seeing his own psychology in the figures he examines, whether that be Leonardo, Michelangelo, Botticelli or any other number of cultural luminaries.

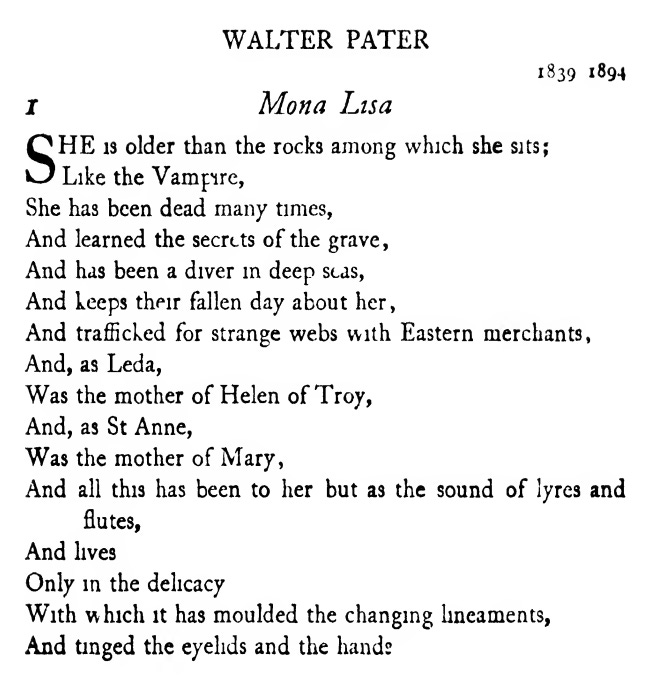

Having taught art history, I know him best for his Studies in the History of the Renaissance, which contains a particularly (in)famous—and, in my mind, unintentionally amusing—passage about the Mona Lisa:

“We all know the face and hands of the figure, set in its marble chair, in that cirque of fantastic rocks, as in some faint light under sea [...] Hers is the head upon which all ‘the ends of the world are come,’ and the eyelids are a little weary. It is a beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh, the deposit, little cell by cell, of strange thoughts and fantastic reveries and exquisite passions. [...] She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary…”

Historian Elyse Graham writes that Pater turns the Mona Lisa into “an emblem of the eternal feminine [...] Pater isn’t giving us a formalist reading. He’s giving us an experience, a demonstration of how it feels for a work of art to so overwhelm the senses that its power seems supernatural.”

Also, I mean, he compares her to a vampire. That’s gold. And oddly not the only time someone has made the comparison. Upon learning that the Mona Lisa had been stolen in 1911, art critic Bernard Berenson bid good riddance: “She had simply become an incubus, and I was glad to be rid of her.”

Pater’s passage caught like wildfire in the culture, with student imitations and famous names riffing on the passage well into the 1900s:

Oscar Wilde, “The Critic as Artist” (1890): “The painter may have been merely the slave of an archaic smile, as some have fancied, but whenever I pass into the cool galleries of the Palace of the Louvre, and stand before that strange figure “set in its marble chair in that cirque of fantastic rocks, as in some faint light under sea”…. I say to my friend, “The presence that thus so strangely rose beside the waters is expressive of what in the ways of a thousand years man had come to desire”; and he answers me, “Hers is the head upon which all ‘the ends of the world are come,’ and the eyelids are a little weary.””

James Joyce, Ulysses (1920): In the episode “Oxen of the Sun,” Joyce apostrophizes Molly as “Our Lady of the Cherries, a comely brace of them pendent from an ear, bringing out the foreign warmth of the skin daintily against the cool ardent fruit.”

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader (1925): “[Pater] is a learned man, but it is not knowledge of Leonardo that remains with us, but a vision, such as we get in a good novel where everything contributes to bring the writer’s conception as a whole before us.”

William Butler Yeats, The Oxford Book of Modern Verse (1936): As seen in the image below, Yeats transforms the passage into free verse.

The Season of Darkness

When I arrived at the right spot with anticipation fiddling my veins and finally laid eyes on Pater’s grave, it was with a thud of the senses. In front of me was a small ziggurat of stones, its writing barely visible through a gauze of decline. The cross that once stood atop the stones was gone, forcibly removed. Pater was born in an East End slum in London. Now, I thought, he has found himself in the memorial equivalent. The fastidious aesthete left to an afterlife of desecration and dilapidation.

I would classify myself as agnostic—I’m skeptical of certainty and would not presume to have the answer about the universe and its mysteries. What I trust most is a specific conception of beauty. The idea that an object, arrangement or attitude and my ‘self’ can synergize, which to me is something like coincidence and a lot like spirituality. A bright spark created from the friction between who I am and, say, the Tube conversations or high-arched ceilings I come across, or the little kindnesses I witness. For not all eyes/brains/hearts/souls are set ablaze by the same beauty; do not find similar clarity of attraction with the same cheekbones or curtain samples.

Pater also believed in beauty as something we feel, “catching glimpses of it in the strange eyes or hair of chance people” (Studies in the History of the Renaissance). To his detriment, perhaps—for ideas about ‘art for art’s sake’ had not yet become mainstream when he was singing its praises in statements like, “experience itself, is the end.” His points of view led many powerful people around him to be skeptical of his intentions; of his very moral and religious fibre. Could his contrarian streak reflect his unchristian character, they wondered? They looked down on his assertions about beauty’s ethical dimensions—even general readers thought these ideas might corrupt the young—and what they saw as strange genre conflations:

“Pater quietly began producing oddball works in genres that mostly didn’t exist: biographies of imaginary people, studies of real people that threw out the facts and kept just the emotional atmosphere, memoirs that seemed to have been processed a few times through hallucination, critical essays that made the critic’s impressions the ground of analysis rather than its instruments.” - Elyse Graham, historian

And it was beauty in one of its many forms, we can assume, that attracted Pater to men such as Richard Jackson, Algernon Swinburne, John Addington Symonds and painter Simeon Solomon. Among a tide of perceived indiscretions, intimate relationships with these and other known homosexuals would put the final nails in Pater’s career coffin, as would his fascination with German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s tendency towards homoeroticism. An old school friend (and perhaps more), John McQueen, betrayed him by making sure the Bishop of London prevented Pater from taking orders in 1862. McQueen’s concern about Pater’s impiety may have been genuine—it is not my place to cast villains without further and often impossible research into motives from the past—but it was undoubtedly detrimental. Subsequently, Oxford authorities used “indiscrete” letters to force him to withdraw his application for a poetry post vacated by Matthew Arnold in 1877 and would react similarly when Pater pursued John Ruskin’s Slade professorship of fine art in 1885. Pater would have a fruitful teaching life, tutoring the likes of Virginia Woolf and poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, but he would never attain the academic heights to which he aspired.

Like a chestnut, Pater let himself out of the soft, spiny shell that offered protection, giving his inner life up for consumption, hoping to be taken elsewhere, to spread into hearts and minds. For those who loved Pater’s work and sensibility, this was a gift to be cherished. A reminder that “To burn always with this hard, gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life.” For others, this was a vulnerability to be crushed.

The Spring of Hope

Perhaps, now that it’s spring, the Friends of Holywell Cemetery will work on a solution to Pater’s desecrated grave. If not, I wonder if Pater’s soul is wounded?

As with all musings in the Internet age, mine has at least one corollary. I came across a 2024 piece by Eva Price in The Oxford Student, in which she too bemoans the state of Pater’s grave and asks, “should it be restored?” Normally, I hate when my novel ideas are inevitably revealed as redundancies, but this time I found it revelatory. Something in the word “restored” made me think of Pater and the society in which he lived. A society that refused to ‘restore’ him to prominence because of who he fundamentally was. Price chooses to see the desecration as a reminder of “life’s beautiful impermanence,” which has its appeal, but I also see it as defiance.

Walter Pater was a man who questioned the status quo, who was not afraid of following his intellectual whims. The cross on top of his grave spoke of the establishment that demoted him, not of any true spiritual leanings he may have had. Its destroyer or thief may have wanted a keepsake, yes, but I prefer to think they were doing Pater a service.

As Elyse Graham writes, “For Pater, the endurance in the body of history and its determining force gives to individual existence the air of tragedy, as though ancient conflicts were determined to play out their final convulsions in individual lives.” Here then, in this hastily lopped off grave, may be the reverberation of Pater’s ‘ancient conflicts.’ So, let the visual reminder of Pater’s life not be the heavy weight of the cross but the solid, minimal form of the ziggurat, a symbol appreciated since at least ancient Mesopotamia and more recently during the Art Deco movement. One could argue that, like Pater’s work, this new headstone iteration is simply well-edited.

Pater preferred spareness in his environment and dress—even his dandyism was relegated to an apple-green tie over his plain gray suit—so perhaps the culprit was Pater himself, his ghost tidying up the fuss.

And perhaps he’s happy that, after all this time, he’s still managing to stand out. At least for those willing to keep looking.

Happy wanderings,

Mikey

So prolific, Mikey. Enjoyed reading what I read, which is most of it.