Sometimes, wandering London feels like exploring a Fragonard painting—Fragonard, the master of escapades in lush, fantastical garden settings. Throughout the city, vines encircle trees in great whorls. Moss grows on brick and casts itself along rooftops. If there’s a surface, there’s vegetation that wants to co-opt it.

More prevalent, it seems, are human interventions. Even in the depths of February, spired Italian cypress trees line walks, sculpted bay and Portuguese laurels frame driveways, palms jazz up front yards. Outside stately homes, climbers are encouraged along walls. Churchyards are brightened by snowdrops. Look closely and you can see daffodils pop their leaves out of the grass in anticipation of spring.

Recently, I visited Kenwood House on the edge of Hampstead Heath. The 17th-century country house is surrounded by flowering shrubs. Rhododendron 'Midwinter' adds a dash of purple and yellow winter aconites huddle beneath a mulberry tree in the Kitchen Garden. Waiting patiently to show off their greenery are towering oaks and beeches and a 350-year-old sweet chestnut (see that and other trees from the historic gardens of English Heritage properties here).

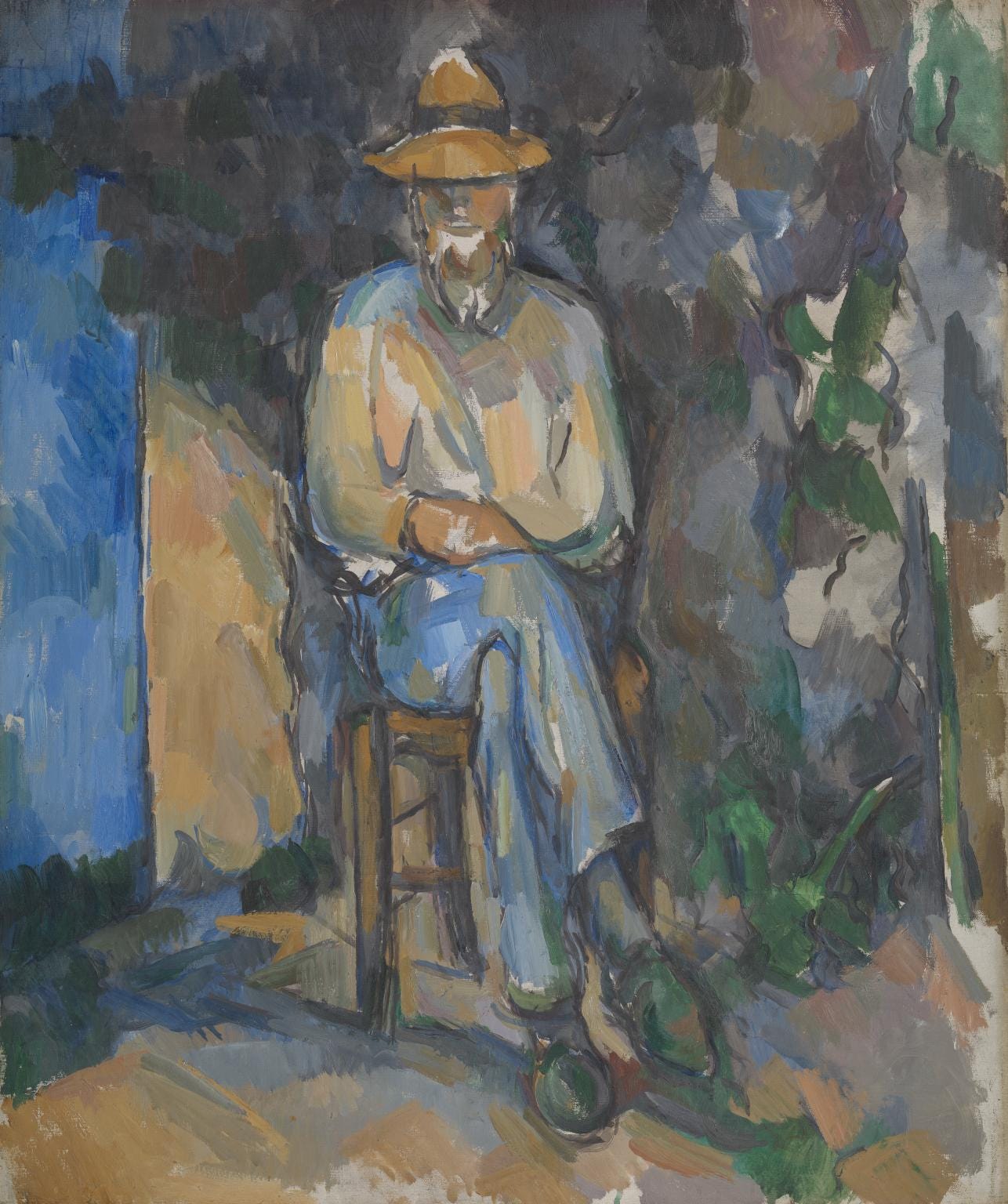

Even indoors at the Tate Modern, one can’t escape the gardens (and why would one want to). No sooner had I entered the first gallery than I came face-to-face with Cezanne’s gardener. Though seated, Vallier appears monumental. At ease in his statuesque pose, one leg crossed over the other. His lanky frame accentuated by the vegetation stretching upwards on his left. The young woman beside me in the gallery succinctly dismissed the painting, saying to her male companion, “I like that one, I like that one,” and when she got to the Cezanne, “I don’t like that one.” It’s hard to say what she so quickly disliked about the work—its rudimentary shapes, its muted tones, its subject—but I’m quite taken by it. There is something charged in capturing this man, someone who toils with his body for a living, in such a relaxed, genteel pose.

It’s official—I have gardens on my mind. And so, it seems, does everyone else, given how they have sprouted in unprecedented numbers over the last few years, providing greener pastures and pastimes for weathering the pandemic and its fallout. Home gardening, loosely defined as the controlled cultivation of outdoor space for sustenance or beauty, has been booming and blooming since 2020. Beyond offering respite from remote work confinement, recent studies show that time with roses and roots propagates more mindfulness, less stress and better sleep. Not to mention a homegrown harvest free of unknown pesticides and sticker shock.

When, I wondered, did humans start to take a shine to this taming of the natural world and what are its ramifications? I decided to do a little digging of my own to find out.

Gardens, a history lesson

c. 10,000 BCE: Gardens proliferate in heavily wetted regions of India and Asia. There, tiered forest gardens provide a nearby food source, privacy, and protection.

c. 8th–6th century BCE: In present-day Iraq, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon earn their spot as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Described at length by Classical authors, the legendary irrigated terraces remain in vogue with the upper classes throughout Ancient Egypt and Rome, where Romans perfect the intricate art of topiary among the crocuses and hyacinth.

c. 500-1500: The war-torn Middle Ages are a time of great decline in gardening. Slowly, Europe emerges from disarray. Monasteries focus on medicinal herbs and altar decorations. Walled pleasure gardens keep out wild animals and preserve seclusion, embellished by raised flower beds and trellises tangled with roses.

1565: Spaniards transport exotic novelties and garden innovations as they settle in St. Augustine, Florida. English colonists arrive half a century later with seeds, which they cultivate alongside Native American crops like beans and squash. Without a systematized way of buying goods, American colonists rely on their own “kitchen gardens” for sustenance and medicinal herbs.

Mid- to Late-1800s: In North America, urbanization and produce markets eliminate the need for kitchen gardens, freeing up space for lawns and ornamental, English-inspired gardens. Elaborate Victorian tastes come and go, followed by humble Arts and Crafts approaches.

1913: The Garden Club of America is founded with the mission to “stimulate the knowledge and love of gardening among amateurs.”

1940s: The bygone concept of kitchen gardens is resuscitated to combat food shortages on the homefront with WWII “victory gardens.” More than 20 million gardens are planted across the United States, accounting for more than 40 percent of produce grown in 1943. The end of the war spells the end of these patriotic food generators.

1950s and 60s: Backyard gardens proliferate as suburbs sprawl, their cultivation made simpler through post-war technology and chemical pesticides.

1990s: Balcony-friendly container gardens take off as urban populations soar.

2009: Michelle Obama breaks ground with a vegetable garden at The White House. Its first since WWII.

March 2020-Today: In response to pandemic-driven hikes in food prices and general stir-craziness, vegetable plots appear in record numbers. Therapeutic gardens soothe those seeking to reconnect to nature and gain reprieve from the news cycle.

Crunching the numbers

2.7%: The boost in sales homeowners saw in 2022 when “landscaping” was mentioned in Zillow listing descriptions. Listings that mentioned “outdoor kitchens” sold for 4.5% more, while “fire pits” stoked property value an extra 2.8%.

26%: The percentage of American consumers who planted a food garden because of the pandemic, according to a market research study by Packaged Goods.

89.3%: The percent of Canadian food gardeners who include tomatoes in their seasonal repertoire, making them by far the most popular crop in Canada—and the U.S.

1,976: Total acreage of the largest garden in the world, which is located in Versailles, France, outside the former palace of King Louis XIV.

2.6 million: The number of times the exotic #dahlia, with its season-long bursts of colour, appears across Instagram. That’s more than quadruple the number of #floralfriday and #flowerfriday hashtagged posts combined.

18.3 million: The number of new gardeners who flooded the market in 2020 in the U.S. alone, according to the National Gardening Survey. On Pinterest, searches for “backyard oasis on a budget” increased by 500%.

Simply put

“To plant a garden is to believe in tomorrow.” – Audrey Hepburn

Home gardens, three ways

Precision à la française: Monet and his Impressionistic gardening aside, the French style follows principles of order and constraint, such as symmetry, proportion, and balance. Schemes are often arranged in careful grids, with hedges as dividers and flowerbeds carved into squares by gravel paths. Terraces, either raised or on higher ground, offer perspectives from above. Skillful gardeners might attempt a knot garden, a geometrically crafted design using aromatic plants and culinary herbs. Not as talented? Ornamental arrangements called parterres, often hemmed in by shapeable boxwoods, can be achieved without the woven effect. Experiment with a restrained colour palette and container planting to polish off the clean, organized look.

English-style wildness: In the 18th century, gardeners and English gentry rebelled against what they saw as the monotony of formal gardens, preferring a “natural” approach akin to rewilding practices advocated by contemporary environmentalists. This style is ideal for those who dig organic beauty. Following Mother Nature’s lead, populate your garden with perennials, poppies, and unkempt grasses, and keep landscaping loose with flowing pathways, interweaving stone walls, vintage furnishings, and water features that double as irrigation. When plants seed across the gravel paths, leave them alone and see what takes root. Low-carbon gardening, which uses locally sourced elements, your own compost, and harvested rainwater, can ensure that your garden is as nature-friendly as it looks.

Low-maintenance Mediterranean: You don’t have to live on the West Coast or a gorgeous Grecian island to channel the mindset of Mediterranean gardeners. The key is water efficiency. Replace sun-bleached lawns with light-coloured gravel and stick with plants local to your area that are adapted to normal rainfall patterns. Shrubs native to the Mediterranean, like lavender, can also survive in winter temperatures as low as -16° C (3° F). Try planting them in the cracks of a rock wall for a touch of scruffy, fragrant beauty, and add hardy prickly-pear cactuses for texture. Create a south-facing stone patio to soak up the sun and punctuate it with bright potted flowers and palms that can be moved inside in colder temperatures. For a thematic flourish, tie in colourful umbrellas, sculptures, and a tiled or tiered fountain that recirculates water.

Have gardens on the mind, too?

Do you have a favourite gardening approach? French-style precision, perhaps, or English-style wildness? Low-maintenance Mediterranean or mixed thematics? Expound upon your preferences in the comments.

Happy wanderings,

Mikey

🙏🏼 Additional content and editorial help on this post by Katie Sehl.

what a perfect antidote to dreary February! While I swoon over precise formal gardens with their clean lines and sharply cut boxwoods, I am a permaculture potager all the way!