"Maine's Wizard of Wood" in Three Timeless Designs

Thomas Moser 101

“It is far more difficult to be simple than to be complicated; far more difficult to sacrifice skill and easy execution in the proper place, than to expand both indiscriminately.” - John Ruskin

I grew up in a small village. “The Prettiest Village in Maine” according to the sign along Route 1. You pass that sign with its cursive assertion on your way to the quaint downtown with its art galleries and antique shops. It would not surprise me if, in one of those establishments, there’s a Thomas Moser design, someone testing its durability or admiring from an artistic distance.

Moser, the champion of traditional craftsmanship and founder of Thos. Moser (with its motto “Handmade American Furniture”), died in early March at the age of 90. News that my parents conveyed to me on our weekly phone call, knowing that I’m a sucker for a design story. And for all my maximalism, I can appreciate simple, sturdy New England design. Moser’s stripped down, unfussy aesthetic screams quintessentially Maine to me. Solid designs for solid people. The Georgetowner went as far as to call him “Maine’s Wizard of Wood.”

But, over time, Moser’s work has been elevated to the status of “functional sculpture,” as Assistant Territory Manager at Thos. Moser puts it. Equally at home at a flea market or auction—though you’re more likely these days to find it for hefty price tags in showrooms from Freeport to San Francisco, or in spaces occupied by bold-faced names. Former President Bill Clinton had a Moser lectern, Steve Jobs had a Moser desk. For the long-running cooking show Simply Ming, the Thos. Moser company first supplied low-back chairs from its Asian-inflected Edo Collection; then, a table and chairs from its Meridian Collection. The latter combining Danish and Shaker influences. Though not in his usual wheelhouse, a wood-grain American flag crafted by Moser denotes the office of Maine’s Republican Senator, Susan Collins.

A thin line: Moser or Thos. Moser?

When to use Moser’s name and when to give credit to ‘the company’? It’s a slippery question, though Thomas Moser himself had a definitive answer: he was adamant his designs were in debt to “the craftsmen and women who make our furniture.”

“They are Thos. Moser,” he insisted, “not me, them.”

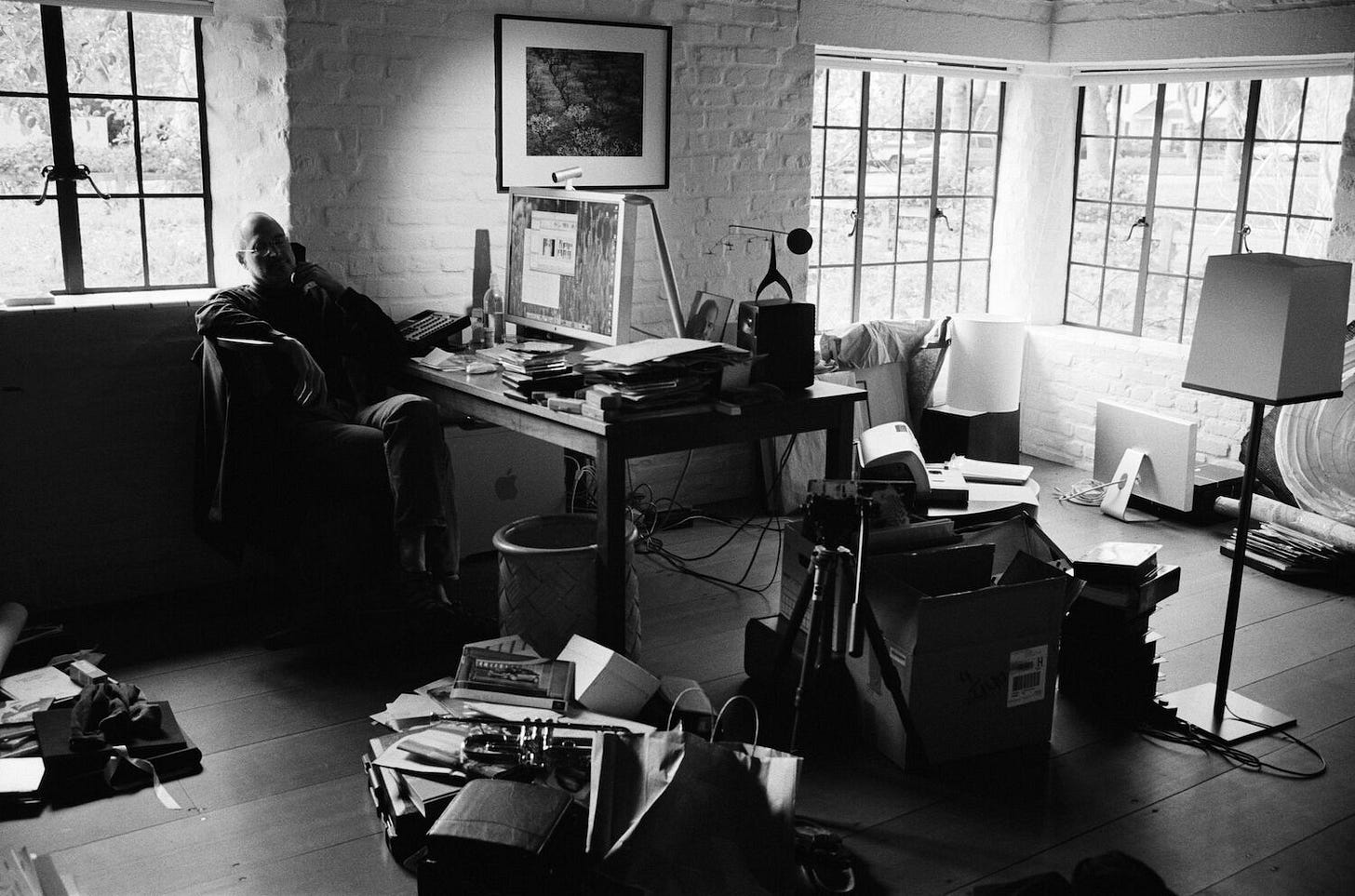

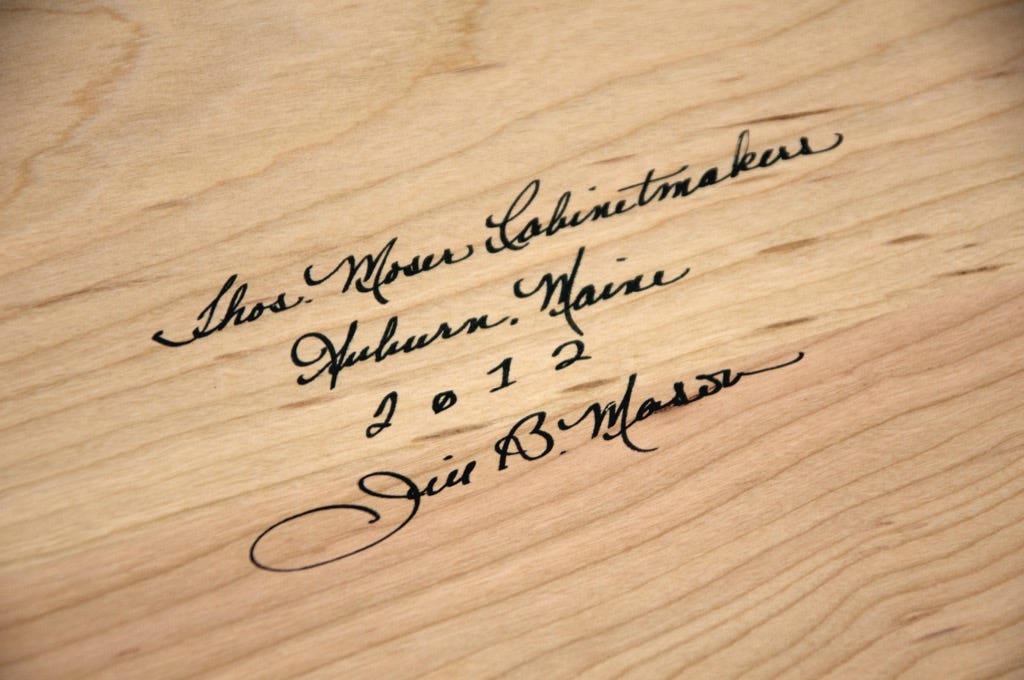

Moser gave his workers leeway to hew to their own style (within reason) on individual projects, choose their own wood-grain, do their own joint-work. This gives each piece a unified soul, he thought. And each craftsperson undertakes the ritual of signing their work when completed. Regardless of Moser’s self-effacing nature, his sensibility steered the collaboration. At the time of his death, it had been years since he had an active building role, but new CEO Philip Hussey points out, “his legacy continues on through everybody he touched, but especially the craftsmen who were lucky enough to work with him.”

So, how did Moser develop his idiosyncratic tastes, eventually rising to “probably the best known living furniture maker” during his over 50-year career? His biography, early influences and design choices tell the story of an Illinois-born, Maine-forged traditionalist. A giant in his industry who curator Donna McNeil calls “a one-of-a-kind type of person [...] credited with the revival of fine woodworking, certainly in Maine, and maybe in the [entire U.S.].”

Thomas Moser, a history lesson

1935-1953: Thomas Francis Moser is born in Chicago and raised in nearby Northbrook, Illinois. Enterprising from a young age, Moser inhabits many roles: Boy Scout, altar boy, golf caddy, window dresser. He remains focused despite the death of his mother when he’s 14 and the subsequent death of his typesetter father on the day Moser turns 18. Before their deaths, he recalls his mother stitching together flour sacks to make pyjamas and his father fermenting homemade wine. That Depression-era thriftiness sticks with him.

1953-1960: For four years, Moser serves as a military policeman in the Air Force, stationed in Greenland far from the home he once knew. After, he returns to the states to study, earning a Bachelor’s degree at SUNY Geneseo. He marries Mary Wilson, a woman he first met when he was 14, and works hands-on jobs tuning organs and repairing antiques.

1950s-60s: Roughly the span of Mid-Century Modernism’s peak popularity. The movement is a mostly Post-WWII trend whose lack of embellishment emphasises clean lines and geometric or organic shapes, which Moser reinterprets in the decades that follow. Though, he moves away from its playful approach to color and mass-produced materials (fiberglass, plastic and plywood), sticking to domestic hardwoods.

1960-1962: While earning an MA from the University of Michigan, Moser builds a home from a Sears catalogue kit. Prefabricated “kit homes” were advertised between 1908 and 1940 in the Sears Modern Homes catalog (so he must have gone diving in a remainders bin).

1966: Moser settles in Maine as a professor of language and speech pathology at Bates College after securing a doctorate in speech communications at UofM and teaching at the State University of New York and later in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, where he set up language labs at the College of Petroleum and Minerals.

“I learned woodworking from dead people.” - Thomas Moser.

1970s:

Moser dabbles in woodworking and antique-hunting as hobbies. He disassembles antique tables and chairs to study the working of the joints and shape of the wood grain, before constructing reproductions out of Maine pine.

After a neighbour buys one of his furniture pieces, he asks for a one-year leave of absence from Bates to pursue the craft. He opens a woodworking shop with his wife in a Shaker community in New Gloucester—one of the last remaining clusters of the egalitarian-minded offshoot of the Quakers.

He elevates a supposedly “cheap” material by making cherry his signature wood, showcasing its rich colour and durability. Cherry eventually surpasses white oak as the No. 1 furniture wood in the U.S.

2002: In Thos. Moser: Artistry in Wood, a book co-written with science writer Brad Lemley, Moser draws from Plato’s concepts of form and ideal to explain the impossible but respectable quest for the “ultimate chairness” of a design. Previous books include How to Build Shaker Furniture (1977) and Thos. Moser’s Windsor Chairmaking (1983).

2007: The Thos. Moser company starts a customer-in-residence program, introducing neophytes to the wonders of woodworking. The program takes them through how to construct a small table or other minor piece.

2008: Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to the White House during the Bush administration occasions Moser to custom-build ceremonial seating in the form of a Harpswell Chair (see “Thomas Moser, three ways” below). In 2015, another Harpswell graces an event for Pope Francis during his two-day stop in Philadelphia.

2015: Maine College of Art’s Institute of Contemporary Art holds a retrospective entitled, Thos. Moser: Legacy in Wood. The exhibit coincides with the release of Moser’s book of the same name, co-written by the curator of the show and former Maine Arts Commission Director, Donna McNeil.

“The exhibit has two objectives: share with others the joy we have known in crafting furnishings that will surely outlive all of us and offer to the student of craft a role model which demonstrates that our national system of enterprise is alive and well, and we all have the freedom to become all that we are capable of being.” - Thomas Moser

2025: In January, Thos. Moser is sold to Chenmark, a family-owned holding company based in Portland, Maine that acquires and operates small businesses. Moser family members continue to operate as “ambassadors” for the brand. CEO Philip Hussey assures the Portland Press Herald, “This happened with Tom’s blessing, in that he wanted to find a way to make sure that Thos. Moser could continue on for the next 50 years.”

Crunching the numbers

$300 USD: The amount of Moser’s first sale: a table he sold to a neighbour.

600: The furthest number of miles the Thos. Moser company will go to source timber for its products (the favourite, of course, being cherry). Moser was a stickler for sustainable methods and local sourcing and spurned the use of imported hardwoods such as teak and mahogany. Any unused pieces are sold to craftsmen or repurposed as firewood or sawdust for animal bedding.

$10,000 USD: The amount for each of five coffee tables Moser signed in March 2007 to celebrate 35 years of the Thos. Moser company. All five sold within three weeks.

$12,500 USD + shipping: Cost of a limited-edition fly-tying desk, which Moser’s designers created in collaboration with the outdoor retailer LL Bean. The desk sold out.

£100,000+: The cost of a 2025 Jaguar F-Type R. In 2015, curator Donna McNeil recalls Moser “driving around in a gold-colored Jaguar and commanding well-earned attention.” (Not entirely “simple living” Shaker behaviour but...)

Simply put

“These days, you can go to IKEA and buy a whole house’s worth of stuff for several thousand dollars and throw it all out in five years. It’s the instant-gratification culture. And that’s the challenge for us.” – Thomas Moser

Thomas Moser, three ways

Harpswell Arm Chair

The love affair between Thos. Moser and the George W. Bush Presidential Center began with the papal visit in 2008, when Harpswell Chairs were spread across the White House’s South Lawn stage, then took off from there.

Among the 55 Thos. Moser pieces—everything from a bench with leather upholstery to a Boat Top Conference Table, custom Credenzas to a Proctors Desk—the Harpswell Chair stands out at the Presidential Center in Dallas, Texas. Chosen to represent American handcrafted furniture, the black walnut chair with leather-covered cushion back and slip seat can be seen as a representation of Moser’s tastes and influences.

Moser’s first spark of inspiration, though?

A decidedly un-American source: a cafe chair he saw while visiting France.

From the get-go, Moser had a vision: “I wanted to recapture the craft of the early 19th-century artisans. I venerate the 19th century.” The mid- to late-1800s being a time of Victorian polymath John Ruskin’s espousal of nature-bound craftsmanship and English textile designer William Morris’ emphasis on the merging of functionality and beauty. Moser owed a great debt to those two monumental men, as well as the Arts and Crafts movement they inspired. Not to mention Germany’s “form follows function” Bauhaus school and the pared-down style of Scandinavian modernism that followed in the wake of the Arts and Crafts movement.

“My work is derivative,” Moser said, never one to mince words.

Harpswell, Maine, where Moser died and where my parents and I spent vacation together last summer, has a jagged coastline full of inlets and is bracketed by nearly 200 islands. Ironic, given that the chair that bears the town’s name is all repeating lines and gentle curves. Even the tapered back legs are hard to clock upon first glance.

From the time Moser opened a woodworking shop in a Shaker community in the 70s, their philosophy infused his output: simplicity and purity. This means:

Lack of pretension and ornamentation (the Harpswell Chair is nothing but frame and upholstery).

Honesty of materials (the wood is not adulterated, the tree’s growth rings visible).

Harmony (sloping shapes repeat throughout the object).

Egalitarian ethos (hence Moser’s collaborative spirit).

Also like the Shakers, Moser prioritized functionality and utility, with each piece of furniture designed for a specific purpose.

“The Shakers prayed to God with their hands.” - Thomas Moser

These humble origins don’t mean that the Harpswell Chairs come cheap. A single chair sells for around $2,200 USD. But Moser always weighed value against time—the longer it takes to make, the longer it lasts, and the higher the justified price tag. An extension of the Shaker axiom Moser often liked to (mis)quote: “Build an object as though it were to last 1,000 years and as if you were to die tomorrow.”

Hunt Chair

North Carolina State University’s Hunt Library has so many iconic seating options—from an Italian mechanical engineer’s Rollingframe Arm Chair to a French architect’s Cassina Aspen Bench, as well as staples of Mid-Century Modern design—that there is an entire Tumblr and book dedicated to them.

With Hunt Library’s over 75 different chairs in 100 different colors, perhaps what makes Moser’s reading chair stand out most is its demureness. It’s upholstered in an understated shade of plum that matches the carpets underfoot. Symmetrical rows of curve-backed chairs made from American black cherry sourced from western Pennsylvania harmonize with an abundance of natural light and sweeping views of tree-rimmed Lake Raleigh.

The goal of the library layout is to create “a fluid transition between the masterplanned landscape to the Hunt Library’s north with the natural environment of Lake Raleigh to the south,” Dezeen reports

According to Architect magazine, the university requested a design for its Quiet Reading Room “that echoed the historical elements of a Bank of England style chair while at the same time remained relevant in what was to be a high-tech and very modern learning space.” The Hunt Chair was the response: “a new interpretation of [Thos. Moser’s] hardworking, long-admired Regent Chair so often employed in academic and office settings—and designed to meet these specific comfort and aesthetic needs.”

How is it made? Mortise-and-tenon construction connects the chair’s legs to its curved back rail while rabbet joinery attaches the seat and legs. Available with or without a seat back.

High Stool

All of Moser’s hallmarks are present in the 2015 design for Park Hyatt Hotel’s Blue Duck Tavern in Washington, DC: clean symmetry, warm wood to enhance the warm and rustic feel of the surroundings, local and sustainable materials to match the local and sustainable ingredients of the restaurant. The handcrafted curves are even more impressive here—one can almost feel the palms molding them. And they echo the organic table edge, giving the High Stool a more modern feel while still retaining an unadorned ease.

To Moser or Not to Moser?

Do you have a favourite Moser design? Are his approaches too stodgy or refreshingly timeless? Sound off in the comments. And as always…

Happy wanderings,

Mikey

Such an amazing article! I’d never heard of this person before, but it was so fascinating to follow the steps of their life story.

Fascinating information, Michael. Thanks for telling us this Moser story who’s from your home state. Certainly a variation from your London wanderings!